Forrest's Final Address To His Troops

Confederate Correspondence, Orders, And Returns Relating To Operations In Kentucky, Southwestern Virginia, Tennessee, Northern And Central Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, And West Florida, From March 16 To June 30, 1865.--#8O.R.--SERIES I--VOLUME XLIX/2 [S# 104]

HEADQUARTERS FORREST'S CAVALRY CORPS,Gainesville, Ala., May 9, 1865.

SOLDIERS: By an agreement made between Lieutenant-General Taylor, commanding the Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana, and Major-General Canby, commanding U.S. forces, the troops of this department have been surrendered. I do not think it proper or necessary at this time to refer to the causes which have reduced us to this extremity, nor is it now a matter of material consequence to us how such results were brought about. That we are beaten is a self-evident fact, and any further resistance on our part would be justly regarded as the very height of folly and rashness. The armies of Generals Lee and Johnston having surrendered, you are the last of all the troops of the C. S. Army east of the Mississippi River to lay down your arms. The cause for which you have so long and so manfully struggled, and for which you have braved dangers, endured privations and sufferings, and made so many sacrifices, is to-day hopeless. The Government which we sought to establish and perpetuate is at an end. Reason dictates and humanity demands that no more blood be shed. Fully realizing and feeling that such is the case, it is your duty and mine to lay down our arms, submit to the "powers that be," and to aid in restoring peace and establishing law and order throughout the land. The terms upon which you were surrendered are favorable, and should be satisfactory and acceptable to all. They manifest a spirit of magnanimity and liberality on the part of the Federal authorities which should be met on our part by a faithful compliance with all the stipulations and conditions therein expressed. As your commander, I sincerely hope that every officer and soldier of my command will cheerfully obey the orders given and carry out in good faith all the terms of the cartel. Those who neglect the terms and refuse to be paroled may assuredly expect when arrested to be sent North and imprisoned. Let those who are absent from their commands, from whatever cause, report at once to this place or to Jackson, Miss.; or, if too remote from either, to the nearest U.S. post or garrison for parole. Civil war, such as you have just passed through, naturally engenders feelings of animosity, hatred, and revenge. It is our duty to divest ourselves of all such feelings, and so far as in our power to do so to cultivate friendly feelings toward those with whom we have so long contested and heretofore so widely but honestly differed. Neighborhood feuds, personal animosities, and private differences should be blotted out, and when you return home a manly, straightforward course of conduct will secure the respect even of your enemies. Whatever your responsibilities may be to Government, to society, or to individuals, meet them like men. The attempt made to establish a separate and independent confederation has failed, but the consciousness of having done your duty faithfully and to the end will in some measure repay for the hardships you have undergone. In bidding you farewell, rest assured that you carry with you my best wishes for your future welfare and happiness. Without in any way referring to the merits of the cause in which we have been engaged, your courage and determination as exhibited on many hard-fought fields has elicited the respect and admiration of friend and foe. And I now cheerfully and gratefully acknowledge my indebtedness to the officers and men of my command, whose zeal, fidelity, and unflinching bravery have been the great source of my past success in arms. I have never on the field of battle sent you where I was unwilling to go myself, nor would I now advise you to a course which I felt myself unwilling to pursue. You have been good soldiers, you can be good citizens. Obey the laws, preserve your honor, and the Government to which you have surrendered can afford to be and will be magnanimous.

N. B. FORREST, Lieutenant-General.

Quote by US President Used in the D.W. Griffith film, “Birth of a Nation.” Said President Wilson, "It is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true." Wilson's family had sympathized with the Confederacy during the Civil War, and cared for wounded Confederate soldiers at a church. When he was a young man, his party had vigorously opposed Reconstruction, and as president he resegregated the federal government for the first time since Reconstruction.

Interview with Nathan Bedford Forrest

Cincinnati Commercial, August 28, 1868 (also 40th Congress, House of Representatives, Executive Documents No. 1, Report of the Secretary of War, Chapter X, Page 193)

Forrest described

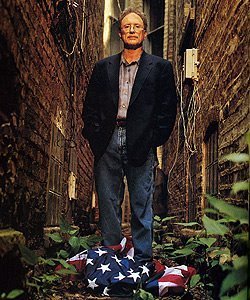

My first visit was to General Forrest, whom I found at his office at 8 o'clock this morning hard at work, although complaining of an illness contracted at the New York convention. Now that the southern people have elevated him to the position of their great leader and oracle, it may not be amiss to preface my conversation with him with a brief sketch of the gentleman. I cannot better personally describe him than by borrowing the language of one of his biographers: "In person he is six feet one inch and a half in height, with broad shoulders, a full chest and symmetrical, muscular limbs, erect in carriage, and weighs 185 pounds; dark gray eyes, dark hair, mustache, and beard worn upon the chin; a set of regular set teeth and clearly cut features," which altogether, makes him rather a handsome man for one forty-seven years of age.

Has no objection to being questioned

After being seated in his office, I said: "General Forrest, I came especially to learn your views in regard to the condition of your civil and political affairs in the State of Tennessee, and the South generally. I desire them for publication in the Cincinnati Commercial. I do not wish to misrepresent you in the slightest degree, and therefore only ask for such views as you are willing that I should publish."

"I have not now," he replied, "and never have had, any opinion on any public or political subject which I would object to having published. I mean what I say, honestly and earnestly and only object to being misrepresented, I dislike to be placed before the country in a false position, especially as I have not sought the reputation which I have gained."

I replied, "Sir, I will publish only what you say, and then you cannot possibly be misrepresented. Our people desire to know your feeling toward the general government, the State of Tennessee, the radical party, both in and out of the State, and upon the question of negro suffrage."

His status defined

"Well, sir," said he, "When I surrendered my 7,000 men in 1865, I accepted a parole honestly, and have observed it faithfully, up to today. I have counseled peace in all the speeches I have made; I have advised my people to submit to the laws of the State, oppressive as they are, and unconstitutional as I believe them to be. I was paroled, and not pardoned until the issuance of the last proclamation of general amnesty, and therefore did not think it prudent for me to take any active part until the oppression of my people became so great that they could not endure it, and then I would be with them. My friends thought differently and sent me to New York, and I am glad that I went there."

The situation getting worse

"Then I suppose, General that you think the oppression has become so great that your people should no longer bear it?"

"No," he answered, "it is growing worse hourly; yet I have said to the people, stand fast; let us try to right the wrong by legislation. A few weeks ago I was called to Nashville to counsel with other gentlemen who had been prominently identified with the cause of the confederacy, and we then offered pledges which we thought would be satisfactory to Mr. Brownlow and his legislature, and we told them that if they would not call out the militia we would agree to preserve order and see that the laws were enforced. The legislative committee certainly led me to believe that our proposition would be accepted, and no militia organized. Believing this, I came home, and advised all of my people to remain peaceful, and offer no resistance to any reasonable law. It is true that I never have recognized the present government in Tennessee as having any legal existence, yet I was willing to submit to it for a time, with the hope that the wrongs might be righted peacefully."

Feeling towards Uncle Sam

"What are your feelings towards the federal government, general?"

"I loved the old government in 1861. I loved the old Constitution yet. I think it is the best government in the world, if administered as it was before the war. I do not hate it; I am opposing now only the radical revolutionists who are trying to destroy it. I believe that party to be composed, as I know it is in Tennessee, of the worst men on God's earth - men who would hesitate at no crime, and who have only one object in view - to enrich themselves."

On Brownlow and the K.K.K.

"In the event of Governor Brownlow calling out the militia, do you think there will be any resistance offered to their acts?" I asked.

"That will depend upon circumstances. If the militia are simply called out, and do not interfere with or molest anyone, I do not think there will be any fight. If, on the contrary, they do what I believe they will do, commit outrages, or even one outrage, upon the people, they and Mr. Brownlow's government will be swept out of its existence; not a radical will be left alive. If the militia are called out, we cannot but look upon it as a declaration of war, because Mr. Brownlow has already issued his proclamation directing them to shoot down the Ku-Klux wherever they find them, and he calls all Southern men Ku-Klux."

"Why, general, we people up north have regarded the Ku-Klux as an organization which existed only in the frightened imagination of a few politicians"

The Ku-Klux Klan

"Well, sir, there is such an organization, not only in Tennessee, but all over the South, and its numbers have not been exaggerated."

"What are its numbers, general?"

"In Tennessee there are over 40,000; in all the Southern states they number about 550,000 men."

"What is the character of the organization; May I inquire?"

"Yes, sir. It is a protective political military organization. I am willing to show any man the constitution of the society. The members are sworn to recognize the government of the United States. It does not say anything at all about the government of Tennessee. Its objects originally were protection against Loyal Leagues and the Grand Army of the Republic; but after it became general it was found that political matters and interests could best be promoted within it, and it was then made a political organization, giving its support, of course, to the Democratic party."

"But is the organization connected throughout the state?"

"Yes, it is. In each voting precinct there is a captain, who, in addition to his other duties, is required to make out a list of names of men in his precinct, giving all the radicals and all the democrats who are positively known, and showing also the doubtful on both sides and of both colors. This list of names is forwarded to the grand commander of the State, who is thus enabled to know who are our friends and who are not."

"Can you, or are you at liberty to give me the name of the commanding officer of this State?"

"No, it would be impolitic."

Probabilities of a Conflict in Tennessee

"Then I suppose that there can be no doubt of a conflict if the militia interfere with the people; is that your view?"

"Yes, sir; if they attempt to carry out Governor Brownlow's proclamation, by shooting down Ku-Klux - for he calls all Southern men Ku-Klux - if they go to hunting down and shooting these men, there will be war, and a bloodier one than we have ever witnessed. I have told these radicals here what they might expect in such an event. I have no power to burn or kill negroes. I intend to kill the radicals. I have told them this and more, there is not a radical leader in this town but is a marked man, and if a trouble should break out, none of them would be left alive. I have told them that they are trying to create a disturbance and then slip out and leave the consequences to fall upon the negroes, but they can't do it. When the fight comes not one of them would get out of this town alive. We don't intend they shall ever get out of the country. But I want it distinctly understood that I am opposed to any war, and will only fight in self-defense. If the militia attack us, we will resist to the last, and, if necessary, I think I could raise 40,000 men in five days ready for the field."

Thinks the K.K.K. beneficial

"Do you think, general, that the Ku-Klux have been of any benefit to the State?"

"No doubt of it. Since its organization, the leagues have quit killing and murdering our people. There were some foolish young men who put masks on their faces and rode over the country, frightening negroes, but orders have been issued to stop that, and it has ceased. You may say, further, that three members of the Ku-Klux have been court-martialed and shot for violations of the orders not to disturb or molest people."

"Are you a member of the Ku-Klux, general?"

"I am not, but am in sympathy and will co-operate with them. I know that they are charged with many crimes that they are not guilty of. A case in point is the killing of Bierfield at Franklin, a few days ago. I sent a man up there especially to investigate the case, and report to me, and I have his letter here now, in which he states that they had nothing to do with it as an organization."

The amnesty

"What do you think is the effect of the amnesty granted to your people?"

"I believe that the amnesty restored all the rights to the people, full and complete. I do not think the federal government has the right to disfranchise any man, but I believe that the legislatures of the States have. The objection I have to the disfranchisement in Tennessee is that the legislature which enacted the law had no constitutional existence, and the law in itself is a nullity. Still, I would respect it until changed by law; but there is a limit beyond which men cannot be driven, and I am ready to die sooner than sacrifice my honor. This thing must have an end, and it is now about time for that end to come."

"An explanation of or excuse for the formation of the Ku-Klux organization made by its defenders, was that it was the natural result of the existence of the 'Loyal Leagues,' secret organizations of Union men. It is reasonable to suppose this may be correct."

Showing posts with label Nathan Bedford Forrest. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Nathan Bedford Forrest. Show all posts

Wednesday, November 5, 2008

"Slap Your Jaws And Force you to resent it." Nathan Bedford Forrest.

Nathan Bedford Forrest to his Commander, General Braxton Bragg

“Slap Your Jaws”

From author Jack Hurst's book on N.B. Forrest, recalling a conversation Forrest had with his commanding officer, General Bragg, surely one of the greatest retorts in American History. This ‘conversation’ took place at General Bragg’s headquarters above Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Forrest entered Bragg’s tent and refused to shake Bragg’s hand. Instead, Forrest stuck the index finger of his left hand into Braggs face and addressed him with frank insubordination.

"I am not here to pass civilities or compliments with you, but on other business.

“You commenced your cowardly and contemptible persecution of me soon after the battle of Shiloh, and you have kept it up ever since.

“You did it because I reported to Richmond facts, while you reported damned lies.

“You robbed me of my command in Kentucky and gave it to one of your favorites ---men that I armed and equipped from the enemies of our country -- in a spirit of revenge and spite, because I would not fawn upon you as others did.

“You drove me into West Tennessee in the winter of 1862 with a second brigade I had organized, with improper arms and without sufficient ammunition, although I had made repeated applications for the same. You did it to ruin me and my career.

“When in spite of all this I returned with my command well equipped by captures, you began again your work of spite and persecution and have kept it up; and now this second brigade, organized and equipped without thanks to you or the government, a brigade which has won a reputation for successful fighting second to none in the army, taking advantage of your position as the commanding general in order to humiliate me, you have taken these brave men from me.

“I have stood your meanness as long as I intend to. You have played the part of a damned scoundrel, and are a coward, and if you were any part of a man I would slap your jaws and force you to resent it.

“You may as well not issue any more orders to me, for I will not obey them, and I will hold you personally responsible for any further indignities you endeavor to inflict upon me. You have threatened to arrest me for not obeying your orders promptly. I dare you to do it, and I say to you that if you ever again try to interfere with me or cross my path it will be at the peril of your life."

Description of Forrest by a CSA infantryman:

“"A tall, lithe, straight figure with the look and tread of an Indian passed swiftly by me, his right arm extended and gesticulating energetically to his men, and his tongue 'keeping time to it,' in a loud, high, harsh voice, every accent full of a commanding will that made his men jump to obedience....Forrest was in full uniform, faded but complete, except the head gear. He wore a home-made, bell-crowned, low, black, beaver hat, wide brimmed. Not very pretty. No man had more right to care for appearances than he, noted Stephenson. Forrest was a handsome man with a face, figure, movement, and bearing that no one, once seeing, was apt to forget. You felt that he was a combination of enormous activity, endurance, and strength. That's what he was! Grace too! Forrest was no country gawk nor awkward man, as rough hewn self made men are apt to be." (1)

"In camp or off duty he was one of the mildest of men in manners and appearance. His voice was soft, his expression gentle, his eyes impassive. When angered, he was terrible, his face was awful to look upon. In battle his rage and excitement was like the frenzy of a madman. Yet the testimony is indisputable that never did he lose his head. His appalling excitement seemed to make his brain work clearer."(2)

In the American Civil War, the last war of great cavalry leaders, names like Stuart, Sheridan, Wheeler, Morgan, Hampton and Buford might come to mind. But the name Forrest seems to stand in a league all to his own. Labeled by some as the untutored genius of the war, Forrest had an unsurpassed record with 30 personal kills in combat. This record, combined with having 29 horses shot from under him during battle, indicates Forrest was never content to lead his men from the rear. With no formal military training, Forrest, like Lincoln and Andrew Jackson, earned his reputation with sheer audacity, instinct and ability.

Not only did he lack formal military training, but had very little formal education in his youth. Forrest was the eldest, and the head of seven brothers and three sisters. His father, a blacksmith, died while Forrest was still a young man, necessitating that he forego a formal education and help to raise the family. As a young business man, Forrest overcame his lack of schooling, entering the war as a private with an estimated wealth of a million and a half. During the war, he was an avid reader, scanning the newspapers daily to keep abreast of military information. His lack of education became most noticeable in his poor spelling and punctuation of personally written dispatches and reports. The words such as "skeer," "git" and "thar" were some examples. Described as urbane and polished in his mannerisms, most of the grammatical distortions in his speech were products of his staff officers and their leg-pulling tales of Forrest. However, in anger or excitement, his no nonsense approach to the English language would become evident. Once, having received a soldier's repeated request for leave, Forrest responded in writing: "I have told you twict goddamit No!"

On the march to Franklin on November 30th 1864, Rev. James McNeilly, Chaplain of Quarles' Brigade, overheard Forrest expressing his disgust over the Federals' escape at Spring Hill to General Walthall. "I saw General Forrest sitting alone on his horse, and I went near him. He seemed to be deeply moved, his face expressive of sorrow, anger and disgust. Directly, General Walthall rode up and saluted him, and then he gave expression to his words: "O General, if I had just one of your brigades, just one, to fling across the road, I could have taken the whole damn shebang."(3)

It was not only this Southern general's victories on the battlefield that made him one of the most colorful and written-about officers of the Civil War, but his eccentric and often controversial behavior ranked him alongside others of a similar nature, such as "Stonewall" Jackson, Bragg and Sherman. His Jekyll-and-Hyde personality made him an interesting study in postwar, and was commented often on by those who fought with him. No doubt his appearance and demeanor were intimidating to many of them. One of his troopers, Captain Dinkins, describes Forrest as being "..a magnetic man...a face that said to all the world: 'Out of my way; I'm coming!'...He was the handsomest man I ever knew." (4) Colonel D.C. Kelley observed Forrest in battle and commented: " The color of his face, which is normally olive or sallow, became flushed and red, not unlike that of a painted Indian Warrior; the eyes flashed with a look that suggested no mercy for any one who showed a disinclination to do promptly what he bid." Indeed, it has been said that Forrest would just as soon kill one of his own men for shirking from duty as an enemy. Forrest abhorred any display of cowardice. An example of this is recounted in John Wyeth's "Life of General Nathan Bedford Forrest."

After crossing the thirty-foot Sakatonchee bridge, under heavy enemy fire, Forrest came upon a frightened Confederate soldier "who, dismounted and hatless, had thrown away his gun and everything else that could impede his rapid flight to the rear." Chalmers, the First Division commander under Forrest, recalled that Forrest jumped down off of his horse, grabbed the frightened trooper, threw him to the ground, and then dragged him to the side of the road, where he began whipping him with a piece of brush. Then turning towards the gunfire, he said" 'Now, God Damn you, you go back there and fight. You might as well get killed there as here, for if you ever run away again you'll not get off so easy.'

Another example is recalled by Private Stephenson, at the battle of Murfreesboro in December of 1864. Forrest was temporarily commanding the infantry of Bate's Division, when the infantry broke and ran from the field in the face of a counterattack. "As we tore along, Forrest was striving to stop the panic. A man came running by breathlessly, hat off, hair flying, eyes bulging, the very picture of panic. His gun was already thrown away, his hands were fingering his belt to fling it and cartridge box off also. 'Halt,' yelled Forrest, leveling his revolver at him! 'Halt!' shouted Forrest again, for the man paid not a particle of attention to him. The half-crazed fellow looked up and kept on his way. Crack went Forrest's pistol, and the fellow pitched forward on his face!" (5)

While his eruptions of temper were feared by his men, they served under him with great loyalty and pride, as did his 16 yr. old son "Willie," who rode with him throughout the war. Most of the regulars of his command learned quickly of his quirks and made great effort to be the recipients of his praise. They also learned when to stay out of his way. Such is the case with one cavalry trooper who learned that lesson painfully. As was a habit of the cavalry general, he would at times analyze his options by walking in circles, his head bowed in concentration, his arms folded behind his back. Those who served under him for any length of time knew better than to interrupt this process. On this occasion in Middle Tennessee, the general was circling an outbuilding when a green trooper wished an audience with him. Each time Forrest made his circle around the building, the trooper would vainly try to get his attention. Upon the third time around, Forrest decided the trooper's persistence was a distraction to his thinking. Without so much as lifting his head, he swung his arm out and clipped the trooper on the jaw. Thereafter, Forrest would nonchalantly step over the prostrate trooper, while he continued his rounds.

Rare were the times that the softer and gentler nature of Forrest was witnessed. But they did indeed exist. It was said that the ferocious warrior on the battlefield was transformed in the presence of children and ladies. Like Robert E. Lee, Forrest delighted in a child's company and held a lifelong affection for youngsters. On the battlefield, his men caught a glimpse of the inner man when his youngest and favorite brother, Jeffrey Forrest was killed.

On February 22, in a running cavalry battle between Forrest and Union Cavalry Gen. William Smith, around Okolona Mississippi, Colonel Jeffrey Forrest was struck in the throat by a ball. "The general rushed to him, raised his head off the ground, and spoke his name several times, "melt[ing] with grief," artillerist Morton later recalled.

Of the many exploits, bold and daring feats that make Forrest the legendary character he is today, his attitude towards his superior officers, in particularly Gen. Braxton Bragg and Gen. Joseph Wheeler, are repeated often with amusement. In General Bragg's case, his seeming delight in purposely arousing Forrest with his petty behavior resulted in one of the most embarrassing moments of his career. For the second time, Bragg ordered Forrest to turn over the command he had worked hard to train to Gen. Wheeler. Riding to his commander's tent, Forrest minced few words with him. "..I have stood your meanness as long as I intend to. You have played the part of a damned scoundrel, and are a coward, and if you were any part of a man I would slap your jaws and force you to resent it...I say to you that if you ever try to interfere with me or cross my path again it will be at the peril of your life." Bragg never muttered a word about the incident, nor sought charges against Forrest.

To General Wheeler, his words were softer in comparison. After an incident in Dover, Tennessee, in which Forrest lost 25 percent of his command under Wheeler's command, Forrest gave Wheeler an ultimatum. "..you've got to put one thing in that report to Bragg," he declared. "Tell him I'll be in my coffin before I'll fight again under your command." It has long been rumored that Hood was also a victim of Forrest's verbal abuse and threats, but there is no evidence to support this. It's safe to say that Forrest held little respect for General Hood during the 1864 Tennessee Campaign. Upon being ordered to join Hood's army by Beauregard, an incident took place that showed just how little. A directive from Hood was sent to Forrest to reduce the army's number of mules per wagon, and ordering all surplus to be turned over to the transportation quartermaster. When Forrest ignored the directive, a Major A. L. Landis paid him a visit. According to John Morton, Landis received this scalding reception: "Go back to your quarters, and don't you come here again or send anybody here again about mules. The order will not be obeyed and moreover, if [the quartermaster] bothers me any further about this matter, I'll come down to his office, tie his long legs into a double bowknot around his neck, and choke him to death with his own shins. It's a fool order anyway.... I whipped the enemy and captured every mule wagon and ambulance in my command; have not made requisition on the government for anything of the kind for two years, and my teams will go as they are or not at all." (6) Fortunately, despite personal likes, Hood placed the rearguard under Forrest's command and it saved the shattered Army of Tennessee from being destroyed on the retreat.

Forrest, the fighter, was a man with a natural instincts in warfare and possessed the killer instinct that intimidated his enemies so. This intimidation was a calculated ploy on the general's part, who often made sure the press accompanied him to embellish his audacity and skill on the battlefield. And when victory was accomplished, the enemy in retreat, Forrest continued to dog their trail relentlessly until both were exhausted. Often referred to as a raider, he proved his mettle in more than one large scale battle such as, Shiloh, Chickamauga and Franklin. What would also prove invaluable to the Confederate armies, was the fact that Forrest would often tie up as many as his own number or more to pursue him. Sherman, also considered a great strategist, said of Forrest; "..he had a genius for strategy which was original, and to me incomprehensible. There was no theory or art of war by which I could calculate with any degree of certainty what Forrest was up to. He always seemed to know what I was going to do next." (7)

Though Forrest admittedly concluded the South had lost the war eighteen months prior to it's official end, he continued to fight with the same determination and spirit right up to the surrender of his command at Cahaba on April 8th 1865. When the Mississippi Governor, Charles Clark and Isham Harris (exiled Governor of Tennessee) approached him to discuss joining unsurrendered Confederates in Texas, Forrest interrupted, "Men" he said, "you may all do as you damn please, but I'm a-going home...To make men fight under such circumstances would be nothing but murder. Any man who is favor of a further prosecution of this war is a fit subject for a lunatic asylum." (8)

And the great cavalry leader did just that, his fame firmly ensured to be written with bold strokes of the pen in our history books. As in his military career, Forrest continued to be surrounded by controversy for the remainder of his life. He continued to be active in civic and political events until his health declined prior to his death. On May 14, 1875 he presence was conspicuous at a reunion of the Seventh Cavalry in Covington. Requested to make a speech, he did so from horseback. "...Comrades, through the years of bloodshed and weary marches you were tried and true soldiers. So through the years of peace you have been good citizens, and now that we are again united under the old flag, I love it as I did in the days of my youth, and I feel sure that you love it also....It has been thought by some that our social reunions were wrong, and that they would be heralded to the North as an evidence that we were again ready to break out into civil war. But I think that they are right and proper, and we will show our countrymen by our conduct and dignity that brave soldiers are always good citizens and law-abiding and loyal people."(9)

On October 29th, 1877, the former President of the Confederate States, Jefferson Davis, came by to visit Forrest at his home in Bailey Springs. But by then Forrest had slipped so far he barely recognized Davis. At 7 p.m., the general breathed his last. Perhaps the most fitting epitaph were the words his friend, Minor Meriwether, was heard to tearfully say to his son Lee, "the man you just saw dying will never die. He will live in the memory of men who love patriotism, and who admire genius and daring." (10)

“Slap Your Jaws”

From author Jack Hurst's book on N.B. Forrest, recalling a conversation Forrest had with his commanding officer, General Bragg, surely one of the greatest retorts in American History. This ‘conversation’ took place at General Bragg’s headquarters above Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Forrest entered Bragg’s tent and refused to shake Bragg’s hand. Instead, Forrest stuck the index finger of his left hand into Braggs face and addressed him with frank insubordination.

"I am not here to pass civilities or compliments with you, but on other business.

“You commenced your cowardly and contemptible persecution of me soon after the battle of Shiloh, and you have kept it up ever since.

“You did it because I reported to Richmond facts, while you reported damned lies.

“You robbed me of my command in Kentucky and gave it to one of your favorites ---men that I armed and equipped from the enemies of our country -- in a spirit of revenge and spite, because I would not fawn upon you as others did.

“You drove me into West Tennessee in the winter of 1862 with a second brigade I had organized, with improper arms and without sufficient ammunition, although I had made repeated applications for the same. You did it to ruin me and my career.

“When in spite of all this I returned with my command well equipped by captures, you began again your work of spite and persecution and have kept it up; and now this second brigade, organized and equipped without thanks to you or the government, a brigade which has won a reputation for successful fighting second to none in the army, taking advantage of your position as the commanding general in order to humiliate me, you have taken these brave men from me.

“I have stood your meanness as long as I intend to. You have played the part of a damned scoundrel, and are a coward, and if you were any part of a man I would slap your jaws and force you to resent it.

“You may as well not issue any more orders to me, for I will not obey them, and I will hold you personally responsible for any further indignities you endeavor to inflict upon me. You have threatened to arrest me for not obeying your orders promptly. I dare you to do it, and I say to you that if you ever again try to interfere with me or cross my path it will be at the peril of your life."

Description of Forrest by a CSA infantryman:

“"A tall, lithe, straight figure with the look and tread of an Indian passed swiftly by me, his right arm extended and gesticulating energetically to his men, and his tongue 'keeping time to it,' in a loud, high, harsh voice, every accent full of a commanding will that made his men jump to obedience....Forrest was in full uniform, faded but complete, except the head gear. He wore a home-made, bell-crowned, low, black, beaver hat, wide brimmed. Not very pretty. No man had more right to care for appearances than he, noted Stephenson. Forrest was a handsome man with a face, figure, movement, and bearing that no one, once seeing, was apt to forget. You felt that he was a combination of enormous activity, endurance, and strength. That's what he was! Grace too! Forrest was no country gawk nor awkward man, as rough hewn self made men are apt to be." (1)

"In camp or off duty he was one of the mildest of men in manners and appearance. His voice was soft, his expression gentle, his eyes impassive. When angered, he was terrible, his face was awful to look upon. In battle his rage and excitement was like the frenzy of a madman. Yet the testimony is indisputable that never did he lose his head. His appalling excitement seemed to make his brain work clearer."(2)

In the American Civil War, the last war of great cavalry leaders, names like Stuart, Sheridan, Wheeler, Morgan, Hampton and Buford might come to mind. But the name Forrest seems to stand in a league all to his own. Labeled by some as the untutored genius of the war, Forrest had an unsurpassed record with 30 personal kills in combat. This record, combined with having 29 horses shot from under him during battle, indicates Forrest was never content to lead his men from the rear. With no formal military training, Forrest, like Lincoln and Andrew Jackson, earned his reputation with sheer audacity, instinct and ability.

Not only did he lack formal military training, but had very little formal education in his youth. Forrest was the eldest, and the head of seven brothers and three sisters. His father, a blacksmith, died while Forrest was still a young man, necessitating that he forego a formal education and help to raise the family. As a young business man, Forrest overcame his lack of schooling, entering the war as a private with an estimated wealth of a million and a half. During the war, he was an avid reader, scanning the newspapers daily to keep abreast of military information. His lack of education became most noticeable in his poor spelling and punctuation of personally written dispatches and reports. The words such as "skeer," "git" and "thar" were some examples. Described as urbane and polished in his mannerisms, most of the grammatical distortions in his speech were products of his staff officers and their leg-pulling tales of Forrest. However, in anger or excitement, his no nonsense approach to the English language would become evident. Once, having received a soldier's repeated request for leave, Forrest responded in writing: "I have told you twict goddamit No!"

On the march to Franklin on November 30th 1864, Rev. James McNeilly, Chaplain of Quarles' Brigade, overheard Forrest expressing his disgust over the Federals' escape at Spring Hill to General Walthall. "I saw General Forrest sitting alone on his horse, and I went near him. He seemed to be deeply moved, his face expressive of sorrow, anger and disgust. Directly, General Walthall rode up and saluted him, and then he gave expression to his words: "O General, if I had just one of your brigades, just one, to fling across the road, I could have taken the whole damn shebang."(3)

It was not only this Southern general's victories on the battlefield that made him one of the most colorful and written-about officers of the Civil War, but his eccentric and often controversial behavior ranked him alongside others of a similar nature, such as "Stonewall" Jackson, Bragg and Sherman. His Jekyll-and-Hyde personality made him an interesting study in postwar, and was commented often on by those who fought with him. No doubt his appearance and demeanor were intimidating to many of them. One of his troopers, Captain Dinkins, describes Forrest as being "..a magnetic man...a face that said to all the world: 'Out of my way; I'm coming!'...He was the handsomest man I ever knew." (4) Colonel D.C. Kelley observed Forrest in battle and commented: " The color of his face, which is normally olive or sallow, became flushed and red, not unlike that of a painted Indian Warrior; the eyes flashed with a look that suggested no mercy for any one who showed a disinclination to do promptly what he bid." Indeed, it has been said that Forrest would just as soon kill one of his own men for shirking from duty as an enemy. Forrest abhorred any display of cowardice. An example of this is recounted in John Wyeth's "Life of General Nathan Bedford Forrest."

After crossing the thirty-foot Sakatonchee bridge, under heavy enemy fire, Forrest came upon a frightened Confederate soldier "who, dismounted and hatless, had thrown away his gun and everything else that could impede his rapid flight to the rear." Chalmers, the First Division commander under Forrest, recalled that Forrest jumped down off of his horse, grabbed the frightened trooper, threw him to the ground, and then dragged him to the side of the road, where he began whipping him with a piece of brush. Then turning towards the gunfire, he said" 'Now, God Damn you, you go back there and fight. You might as well get killed there as here, for if you ever run away again you'll not get off so easy.'

Another example is recalled by Private Stephenson, at the battle of Murfreesboro in December of 1864. Forrest was temporarily commanding the infantry of Bate's Division, when the infantry broke and ran from the field in the face of a counterattack. "As we tore along, Forrest was striving to stop the panic. A man came running by breathlessly, hat off, hair flying, eyes bulging, the very picture of panic. His gun was already thrown away, his hands were fingering his belt to fling it and cartridge box off also. 'Halt,' yelled Forrest, leveling his revolver at him! 'Halt!' shouted Forrest again, for the man paid not a particle of attention to him. The half-crazed fellow looked up and kept on his way. Crack went Forrest's pistol, and the fellow pitched forward on his face!" (5)

While his eruptions of temper were feared by his men, they served under him with great loyalty and pride, as did his 16 yr. old son "Willie," who rode with him throughout the war. Most of the regulars of his command learned quickly of his quirks and made great effort to be the recipients of his praise. They also learned when to stay out of his way. Such is the case with one cavalry trooper who learned that lesson painfully. As was a habit of the cavalry general, he would at times analyze his options by walking in circles, his head bowed in concentration, his arms folded behind his back. Those who served under him for any length of time knew better than to interrupt this process. On this occasion in Middle Tennessee, the general was circling an outbuilding when a green trooper wished an audience with him. Each time Forrest made his circle around the building, the trooper would vainly try to get his attention. Upon the third time around, Forrest decided the trooper's persistence was a distraction to his thinking. Without so much as lifting his head, he swung his arm out and clipped the trooper on the jaw. Thereafter, Forrest would nonchalantly step over the prostrate trooper, while he continued his rounds.

Rare were the times that the softer and gentler nature of Forrest was witnessed. But they did indeed exist. It was said that the ferocious warrior on the battlefield was transformed in the presence of children and ladies. Like Robert E. Lee, Forrest delighted in a child's company and held a lifelong affection for youngsters. On the battlefield, his men caught a glimpse of the inner man when his youngest and favorite brother, Jeffrey Forrest was killed.

On February 22, in a running cavalry battle between Forrest and Union Cavalry Gen. William Smith, around Okolona Mississippi, Colonel Jeffrey Forrest was struck in the throat by a ball. "The general rushed to him, raised his head off the ground, and spoke his name several times, "melt[ing] with grief," artillerist Morton later recalled.

Of the many exploits, bold and daring feats that make Forrest the legendary character he is today, his attitude towards his superior officers, in particularly Gen. Braxton Bragg and Gen. Joseph Wheeler, are repeated often with amusement. In General Bragg's case, his seeming delight in purposely arousing Forrest with his petty behavior resulted in one of the most embarrassing moments of his career. For the second time, Bragg ordered Forrest to turn over the command he had worked hard to train to Gen. Wheeler. Riding to his commander's tent, Forrest minced few words with him. "..I have stood your meanness as long as I intend to. You have played the part of a damned scoundrel, and are a coward, and if you were any part of a man I would slap your jaws and force you to resent it...I say to you that if you ever try to interfere with me or cross my path again it will be at the peril of your life." Bragg never muttered a word about the incident, nor sought charges against Forrest.

To General Wheeler, his words were softer in comparison. After an incident in Dover, Tennessee, in which Forrest lost 25 percent of his command under Wheeler's command, Forrest gave Wheeler an ultimatum. "..you've got to put one thing in that report to Bragg," he declared. "Tell him I'll be in my coffin before I'll fight again under your command." It has long been rumored that Hood was also a victim of Forrest's verbal abuse and threats, but there is no evidence to support this. It's safe to say that Forrest held little respect for General Hood during the 1864 Tennessee Campaign. Upon being ordered to join Hood's army by Beauregard, an incident took place that showed just how little. A directive from Hood was sent to Forrest to reduce the army's number of mules per wagon, and ordering all surplus to be turned over to the transportation quartermaster. When Forrest ignored the directive, a Major A. L. Landis paid him a visit. According to John Morton, Landis received this scalding reception: "Go back to your quarters, and don't you come here again or send anybody here again about mules. The order will not be obeyed and moreover, if [the quartermaster] bothers me any further about this matter, I'll come down to his office, tie his long legs into a double bowknot around his neck, and choke him to death with his own shins. It's a fool order anyway.... I whipped the enemy and captured every mule wagon and ambulance in my command; have not made requisition on the government for anything of the kind for two years, and my teams will go as they are or not at all." (6) Fortunately, despite personal likes, Hood placed the rearguard under Forrest's command and it saved the shattered Army of Tennessee from being destroyed on the retreat.

Forrest, the fighter, was a man with a natural instincts in warfare and possessed the killer instinct that intimidated his enemies so. This intimidation was a calculated ploy on the general's part, who often made sure the press accompanied him to embellish his audacity and skill on the battlefield. And when victory was accomplished, the enemy in retreat, Forrest continued to dog their trail relentlessly until both were exhausted. Often referred to as a raider, he proved his mettle in more than one large scale battle such as, Shiloh, Chickamauga and Franklin. What would also prove invaluable to the Confederate armies, was the fact that Forrest would often tie up as many as his own number or more to pursue him. Sherman, also considered a great strategist, said of Forrest; "..he had a genius for strategy which was original, and to me incomprehensible. There was no theory or art of war by which I could calculate with any degree of certainty what Forrest was up to. He always seemed to know what I was going to do next." (7)

Though Forrest admittedly concluded the South had lost the war eighteen months prior to it's official end, he continued to fight with the same determination and spirit right up to the surrender of his command at Cahaba on April 8th 1865. When the Mississippi Governor, Charles Clark and Isham Harris (exiled Governor of Tennessee) approached him to discuss joining unsurrendered Confederates in Texas, Forrest interrupted, "Men" he said, "you may all do as you damn please, but I'm a-going home...To make men fight under such circumstances would be nothing but murder. Any man who is favor of a further prosecution of this war is a fit subject for a lunatic asylum." (8)

And the great cavalry leader did just that, his fame firmly ensured to be written with bold strokes of the pen in our history books. As in his military career, Forrest continued to be surrounded by controversy for the remainder of his life. He continued to be active in civic and political events until his health declined prior to his death. On May 14, 1875 he presence was conspicuous at a reunion of the Seventh Cavalry in Covington. Requested to make a speech, he did so from horseback. "...Comrades, through the years of bloodshed and weary marches you were tried and true soldiers. So through the years of peace you have been good citizens, and now that we are again united under the old flag, I love it as I did in the days of my youth, and I feel sure that you love it also....It has been thought by some that our social reunions were wrong, and that they would be heralded to the North as an evidence that we were again ready to break out into civil war. But I think that they are right and proper, and we will show our countrymen by our conduct and dignity that brave soldiers are always good citizens and law-abiding and loyal people."(9)

On October 29th, 1877, the former President of the Confederate States, Jefferson Davis, came by to visit Forrest at his home in Bailey Springs. But by then Forrest had slipped so far he barely recognized Davis. At 7 p.m., the general breathed his last. Perhaps the most fitting epitaph were the words his friend, Minor Meriwether, was heard to tearfully say to his son Lee, "the man you just saw dying will never die. He will live in the memory of men who love patriotism, and who admire genius and daring." (10)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)